23 December, 2020The Covid-19 outbreak is changing how we work and white collar workers are particularly affected. For white-collar workers, the future of work has already arrived and unions have to address the changes.

“As industries are becoming increasingly automated, there will be more white-collar workers; the technological transformation is blurring the lines between blue and white-collar workers. With Industry 4.0 and increasingly telework or online work, white-collar work risks becoming more increasingly stressful with no clear division between work and free time, a rapid change of skills and a constant pressure to readjust.

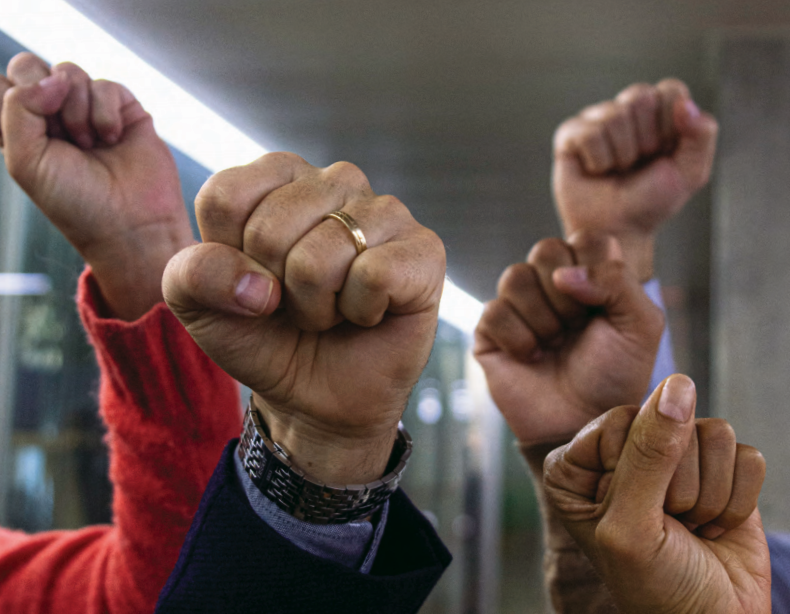

"Unions must organize and meet the needs of all workers, and regulate new ways of working,”

says Atle Høie, IndustriALL Global Union assistant general secretary.

The pandemic has brought increasing unemployment among white-collar workers as well. In India, white-collar experienced the biggest job loss; in Sweden, Unionen reports a rise in unemployment among consultants and workers in small companies. The CGC-CFE reported an increased number of dismissals among their members. Subcontracted workers are more affected as it is hard for these small and medium companies to withstand the economic downturn. The situation may worsen next year and it is unclear what employment will be like for these workers.

At the start of 2020, less than five per cent performed their jobs remotely, according to WEF. Today, more than half of high-skilled workers work remotely, and widespread telework may become a permanent feature. According to the report, 84 per cent of employers are set to rapidly digitalize the working processes, including a significant expansion of remote work—with the potential to move 44 per cent of their workforce to operate remotely.

According to surveys conducted by employers and trade unions among workers who have been working from home since the outbreak of the pandemic, workers would be keen to continue teleworking several days a week, citing autonomy and flexibility among the main reasons.

Issues that came up such as lack of proper IT material, poor ergonomic environment for workers, when establishing the teleworking at a large scale so quickly in March this year highlight the need for proper planning and regulation.

ITUC’s Legal Guide on Telework summarizes the new concerns to be addressed, including ergonomic strains; the emergence of psychosocial health and safety risks linked to isolation from colleagues; issues related to workers’ privacy given that the employers’ ability to use electronic surveillance is enhanced; limit the career advancement of workers, particularly women; associated risk of domestic violence; blurred limit between work and family life and associated increased stress mainly for women workers; limited role of the labour inspectorates, making the enforcement of labour laws more challenging.

Unions need to urgently bargain new agreements to regulate telework. New legislation and agreements on telework have been negotiated. The ILO has published a practical guide on teleworking during the pandemic and beyond. Trade unions, like Unite in UK, have developed guidelines and model agreements.

Trade unions will also have to adapt to these new working conditions. How do unions perform their work when workers are working remotely? How to ensure that remote work will not be an excuse to move work to countries where workers’ rights are not respected?

The current crisis, together with new technologies, has made companies re-think ways of working and may contribute to an increase of crowdwork among white-collar workers. Crowdwork emerged in the early 2000s and is an outsourcing of work to a large pool of online, geographically dispersed, workers by the intermediary of digital platforms that provide the technical infrastructure for requesters to advertise tasks to potential workers.

In addition to matching clients and workers, the platforms also handle contracting, time tracking, monitoring, billing and dispute resolution, allowing the entire relationship to be carried out remotely. Jobs range from sophisticated computer programming, data analysis and graphic design to relatively straightforward microtasks of a clerical nature.

It is difficult to get data on the extent of crowdwork, but according to the ILO, the online labour market growing by 25.5 per cent between July 2016 and June 2017.

The majority of employers are located in high-income countries while most of the workers are located in low- and middle-income countries. The largest share of online labour demand, 41 per cent, originates from employers based in the United States.

The pandemic has shown the potential of a digital workforce. Companies might now favour remote online contractors hired through web-based platforms over on-site contractors hired through conventional staffing agencies. For example, for IT set up and maintenance of digital tools, if large firms have existing IT services outsourcing providers, small- and medium-sized companies may be turning to online labour platforms for these needs.

Workers resort to crowdwork looking for more flexibility and autonomy, or additional pay from another job, or they could simply not find traditional work. Advantages associated with crowdwork should not hide the precariousness and insecurity of this form of employment, as well as the low or inexistent social protection. Furthermore, this way of working may exacerbate the gender inequalities.

Most crowdwork is not subject to labour regulations, so workers have little control over when they will have work or their working conditions. They also have limited options for recourse in cases of unfair treatment.

IndustriALL affiliates are defending the rights of crowd- and platform workers and taking action to improve working conditions in several countries. In 2015, unions launched FairCrowdWork.org, which collects information about crowd work, app-based work, and other platform-based work from workers and unions. The site offers ratings of working conditions on different online labor platforms based on surveys with workers. It is a joint project of the Austrian Chamber of Labor, the Austrian Trade Union Confederation and Unionen.

In 2017, IG Metall, the signatory platforms, and the German Crowdsourcing Association established an Ombuds office to enforce a Code of Conduct and resolve disputes between workers and signatory platforms. The Ombuds office, handled by IG Metall, resolves any disputes.

“Unions need to take innovative action to address white-collar workers’ needs and concerns if we are to organize more white-collars and adapt and frame the future of work,”

says Atle Høie.