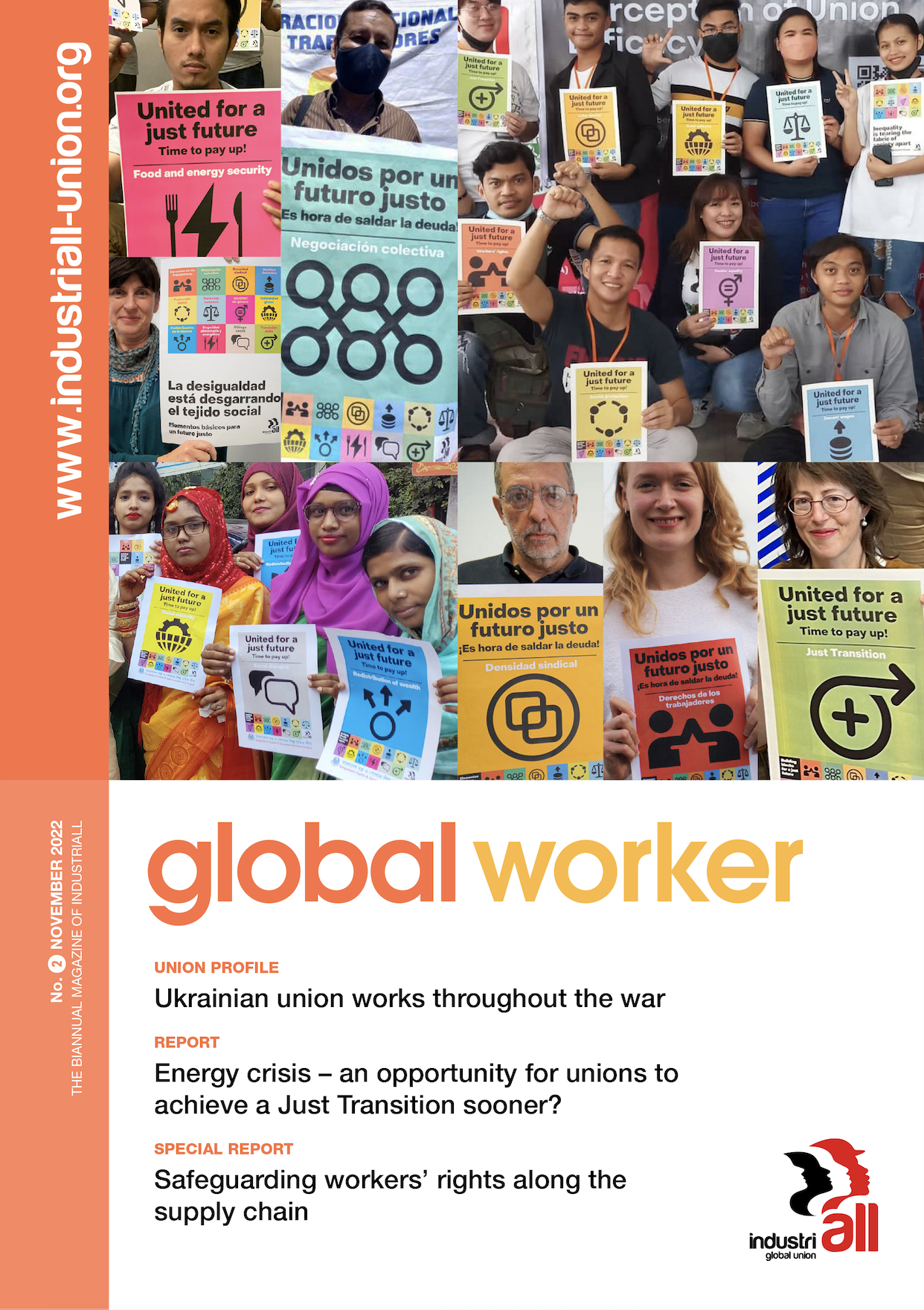

16 January, 2023After the Covid-19 induced crisis of the last three years, uncertainty continues for millions of workers globally, as the working class is in the grip of a low wage crisis.

Feature From Global Worker no 2 November 2022 |   |

| Region: Africa & Asia Theme: the wage crisis Text: Kalyani Badola & Elijah Chiwota |

The situation is dire for textile, garment, shoe, and leather workers in the Global South, who are working under precarious conditions of declining real wages and wage stagnation.

The textile and garment workers in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa are facing the brunt of the low wage crisis and living in poverty despite having full-time jobs. What the workers earn is not enough to buy food, pay for housing, transport to go to work, pay for childcare and school fees, and other daily expenses whose prices are skyrocketing. The average inflation rate around the world currently is about seven percent – a huge leap when compared to the four and three per cent in 2020 and 2021 respectively. In extreme cases such as Zimbabwe, inflation is an astronomical 280 per cent.

The wage crisis precedes the Covid-19 pandemic. In 2018, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) published a report on the unprecedented wage stagnation across the globe. This was confirmed by the International Labour Organisation’s (ILO) Global Wage Report 2020-2021, which states that the rate of inflation in the Asia Pacific region stood at 4.52 per cent in 2017, 3.33 per cent in 2018, and 3.63 per cent in 2019. However, the average real wage increase, for the corresponding period was 1.8, 1.6 and 1.7 per cent, clearly showing that wage increases did not match inflation.

But the underpaid workers were productive as companies made profits while wages declined across the board. The ILO report highlights that in the South Asian region, labour productivity growth rose between 2010 and 2019, but the actual minimum wage growth trailed behind. For example, In Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, there was negative wage growth in the last ten years. The report also highlights that in 2019 the minimum wage in Bangladesh did not even reach the lowest international poverty line of U$2.15 per person per day.

The situation is now more precarious for workers with the high inflation across the region. Food inflation rose to 95 per cent in Sri Lanka in September. In Pakistan, food inflation touched 32 per cent as the country continues to struggle with the destruction caused by the massive floods that worsened already surging prices.In Bangladesh and Nepal, the inflation rate is around nine per cent.

Women workers in the garment and textile industries were the worst affected by the low wages, and inefficient and inadequate regulation led to poor social security. Most workers resorted to cutting meals, withdrawing their children from schools, or borrowing at very expensive interest rates. Another ILO report also found that the median income among garment workers dropped in terms of real wages when they returned to work when factories reopened after Covid-19 lockdowns, making it near impossible to meet the cost-of-living standards across South and Southeast Asia. The situation hasn’t improved since.

For instance, in Sri Lanka, garment workers are paid as low as LKR16000 (US$44), the national minimum wage which hasn’t been revised to keep pace with the rising inflation. The national minimum wage in Bangladesh was last revised four years ago and currently stands at BDT8000 (US$79). These minimum wages come nowhere close to living wages required to maintain decent living standards.

In Pakistan, after a sustained campaign by IndustriALL affiliates and workers in the carpet industry, the Punjab Government announced a wage increase of PKR2500 (US$11) for industrial workers in June 2021. But as employers refused to comply with the government order unions had to resort to direct action and for more than six months, workers fought to get the government-mandated wages.

In Sri Lanka, affiliates have been demanding that the minimum wage be raised to LKR26, 000 (US$71) per month. Unions have submitted several memorandums to the Sri Lankan government, but their demands are yet to be met. Affiliates are organizing community kitchen programmes to address the massive food inflation. Unions have also taken to the streets in Nepal and Bangladesh, demanding that the governments address the wage crisis amidst such high inflation and that workers must be paid living wages.

Unions’ experiences in the region show that in workplaces where workers negotiate long-term wage settlements, employers delay entering into deals and by the time the agreement is signed, the wage rise would have fallen far behind inflation and workers lose out.

Across the Indian Ocean, in Sub Saharan Africa, for many years textile and garment workers, over 80 per cent of whom are women, have been campaigning for living wages but with limited success as the wages have remained low.

The top textile and garment producing countries exporting to the US under the African Growth and Opportunity Act are Kenya, Lesotho, Madagascar, Mauritius, Tanzania, South Africa, Ghana, Nigeria and Eswatini. Ethiopia is on suspension because of the war in the Tigray region. Like in South Asia, the stagnation of the wages worsened during the Covid-19 pandemic, which saw some factories scaling down production or closing operations while the statutory minimum wages in most countries were lower than the living wages that workers required for a decent living.

According to IndustriALL affiliates in Ethiopia, Madagascar and Zimbabwe, workers earn wages of less than US$2.15 per day. At less than US$30 per month, Ethiopia has the lowest wages in the textile and garment industry globally. Often the poor wages are accompanied by no benefits, and the absence of social security. Further, most employers that pay low wages are serial violators of workers’ rights to freedom of association and collective bargaining. Although workers are bullied and put under pressure to meet production targets, they remain underpaid.

“We are treated so badly. I find it hard to believe that I earn an entry level wage after 15 years as a machinist,” says a Madagascar textile worker who earns 200 000 Ariary or US$46 per month.

Shop stewards and union members are often targeted for dismissals and other forms of intimidation and harassment if they demand better wages. Additionally, young women face gender-based violence and harassment, as has been reported in Ethiopia, Lesotho, and Madagascar. Supervisors use the low wage crisis as an opportunity to sexually exploit workers by asking for sex in exchange for overtime work and promotion to permanent contracts. Sex for jobs during interviews is also common and has been reported in many countries in the region.

In Ethiopia, young women share accommodation, and it is not unusual for four workers to share a single room to stretch their meagre earnings until the next pay day. This is attributed to the low wage model that the country has been using to attract foreign direct investment into the country.

Wage underpayments and theft have been reported in Zimbabwe, where workers go for months without getting paid wages. With inflation hovering over 280 per cent, over 60 per cent of the workforce earns less than US$51 per day, according to Zimbabwe Statistics the national agency responsible for data collection. To make matters worse, some employers have closed shop and disappeared without paying wages and retrenchment benefits to the workers.

Unions are continuing to organize and campaign for living wages, strengthening collective bargaining at the company and industry level, and demanding statutory wage fixing that considers workers’ demands for living wages. Unions are also fighting against precarious working conditions and promoting direct employment of permanent workers. They are also confronting contract work, labour broking subcontracting and other non-standard forms of employment that are contributing to the low wages’ crisis. Unions want minimum wage regulations to include living wages.

Workers have gone on strike and picketed for better wages in the textile and garment sector in Eswatini and Lesotho. The minimum wages in these countries are low. A machinist earns LSL23o7 (US$126) according to the Lesotho Government Gazette while in Eswatini she earns SZL2000 (US$109). In Eswatini, the government is colluding with employers and using violence against striking workers, including teargassing workers and arson attacks on union leaders’ homes.

Possible strategies to protect workers against low wages

In South Africa, the Southern African Clothing and Textile Workers Union (SACTWU) has successfully negotiated agreements in the textile and garment sectors with industry bargaining councils and employer associations to push back against poverty wages.

Government policies that promote the decent work agenda – job creation, workers’ rights, social dialogue, and social protection – can also help in the living wage campaigns. Statutory minimum wages that consider the cost of living and inflation are also important for the achieving of better wages.

Globally, the ACT initiative, an agreement between global brands and trade unions, aims to achieve living wages in the textile and garment shoe and leather sectors through promoting collective bargaining at industry level, which is a strategy that can be used for living wages in South Asia and SSA. ACT is currently operating in three garment-producing countries – Bangladesh, Cambodia, and Turkey. In Bangladesh, a dispute resolution mechanism has been set up, and meetings are scheduled with brands, the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) and trade unions.

Additionally, in factories that supply companies that have signed Global Framework Agreements (GFAs) with IndustriALL Global Union, including Asos, H&M, Inditex and others, there are efforts to engage on social dialogue to improve wages and working conditions. The social dialogue and collective bargaining are aimed atdecent living standards and promoting workers’ rights in the supply chain. The GFAs are expected to ease the low wage crisis in some countries like Mauritius and Madagascar as brands want their suppliers to pay better wages.

GFAs have proven useful by pushing global garment brands to ensure that manufacturers in the South Asian region negotiate better wages with unions and can help to build the collective bargaining power of trade unions.