7 August, 2025In Pittsburgh on 4-7 August, 2025 , IndustriALL affiliate,The United Steelworkers (USW) brought together more than 200 delegates from refineries, pipelines, and chemical plants across the United States for the National Oil Bargaining Conference (NOBC). Held every two years, this event sets the stage for national-level negotiations in the oil sector. But as delegates gathered this year, it became clear that the forces shaping their negotiations, and the futures of their jobs, are increasingly global, technological, and unpredictable.

A coordinated model of bargaining

The National Oil Bargaining Program, established in 1965, is a unique example of structured union coordination. It brings bargaining units together to align contract timelines and build a common platform. Proposals from local councils are reviewed and consolidated by a rank-and-file National Policy Committee, which then enters negotiations with Marathon Petroleum, the lead employer.

Once a national agreement is reached, it becomes the pattern for all participating companies and sets a minimum standard across the industry. This structured approach prevents fragmentation and strengthens bargaining power.

Mike Smith (USW) adressing Conference (NOBC)

“Your presence here is an investment in our future. The time we spent together sharing strategies and building solidarity will determine the strength we take into bargaining,”

said Mike Smith, national oil bargaining program chair.

The program’s strength lies in unity and timing, ensuring that companies cannot play workers or worksites against one another. While this model is specific to the U.S., its underlying principle, building collective power through coordination, offers lessons for unions globally.

Global pressures on national negotiations

The context surrounding the 2025 conference was shaped by a broader sense of uncertainty. During the opening session, union leaders highlighted key challenges facing the sector, including the rollback of promised investment in future energy technologies like hydrogen and carbon capture, rising inflation, tariffs, and international instability. These factors are already leading many companies to delay or reduce investment in their facilities, despite continued profitability in the refining sector. Delegates were urged to bear these dynamics in mind as they prepare for the upcoming round of negotiations.

“We’ve seen a lot of canceling of funding… the global market is kind of unknown,”

said Smith.

Much of this instability stems from the shift in U.S. federal energy policy between administrations. Under President Biden, the sector saw significant investment linked to clean energy expansion and industrial transition. But with the change in political climate and expectations of deregulation under Trump’s return to influence, many companies have withdrawn funding or frozen projects. Workers now find themselves caught between two competing visions of the energy future, with little say in either.

Delegates also raised concerns about rising health care costs, inflation, severance protections, retirement security, and job stability, all of which will be central to negotiations starting in January 2026.

In an industry still grappling with post-COVID instability, it is clear that economic and political volatility is being offloaded onto workers. The question at the core of this year’s negotiations is: who pays the price when energy companies shift priorities?

Technology and exclusion from transition

As the industry evolves, so too do the threats, and they are not only economic. Diana Junquera Curiel, IndustriALL’s energy industry and Just Transition director, addressed the growing risks of workers being excluded from key decisions on energy transition and technological change. She warned that artificial intelligence (AI), deregulation, and emerging trade deals are reshaping the sector at a rapid pace.

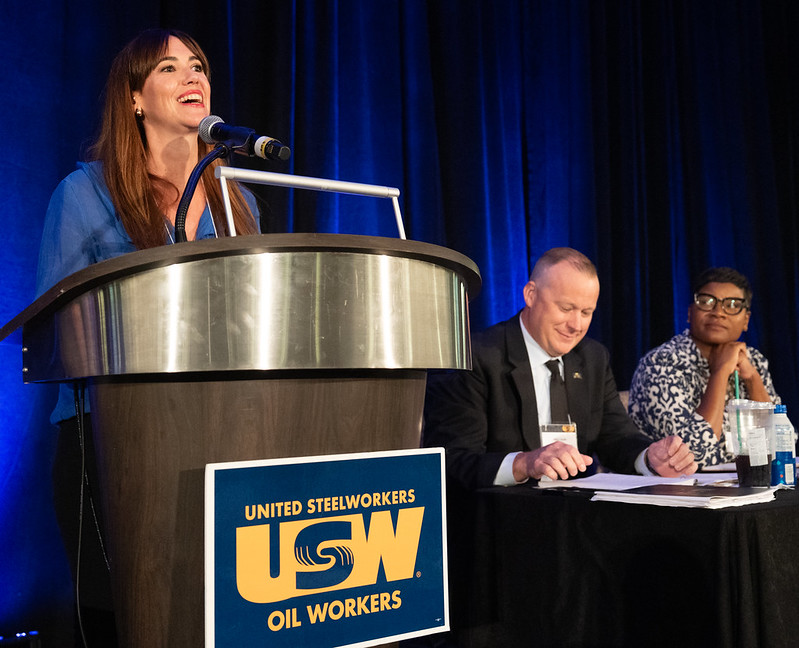

Diane Junquera-Curiel adressing NOBC in Pittsburgh

“Energy companies are already using AI in their processes, I analyzed the risks and opportunities of AI in the sector. Unions must be at the table in technological transitions,”

said Junquera Curiel.

Across the oil sector, AI is increasingly being used for predictive maintenance, process automation, and even safety monitoring. While these technologies can improve efficiency, they also pose serious threats to job security, skill requirements, and oversight, especially when introduced without worker input or bargaining.

She stressed that outcomes in the United States have global implications:

“Your battles and negotiations here in the United States don’t just stay in Texas, California, or Pennsylvania. They ripple across oceans, shaping the realities of oil workers in the UK, Nigeria, Mexico, and beyond.”

The outcomes of U.S. national bargaining talks often set precedents that companies mirror in other parts of the world. When U.S.-based multinationals negotiate wages, safety standards, or severance protections at home, they frequently influence what is offered, or withheld, at facilities they operate or contract in the Global South. Moreover, global supply chains are tightly interlinked; if U.S. refineries face labour disruptions or win gains that increase costs, those effects are often passed down to workers in outsourced or subcontracted operations abroad. For unions in countries where labour protections are weaker or union density is lower, U.S. union victories can offer leverage, or put pressure on them to defend gains. That’s why global coordination and solidarity remain essential.

Safety, recognition, and resilience

USW International vice president and IndustriALL vice president, Roxanne Brown, warned of cuts to key safety institutions such as the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), which would limit inspections and weaken enforcement, putting workers at increased risk.

Roxanne Brown (USW) and IndustriALL VP adressing NOBC

“Thank you, oil workers, for everything you do every single day, the unsung heroes who keep this country running. From the energy that powers our homes to the materials in everyday products, your work touches every American life, and it’s time the nation recognized it,”

said Brown.

Delegates affirmed that health and safety must remain a priority at the bargaining table.

With reduced oversight and growing automation, workers are increasingly expected to monitor their own safety in high-risk environments. Strengthened safety language in collective agreements is therefore not just protective, it is essential.

International perspectives and shared challenges

The conference also hosted international labour leaders who provided critical perspectives on the global energy landscape.

Frode Alfheim (Styrke) adressing NOBC

Frode Alfheim, President of Norwegian union Styrke (formerly Industri Energi), highlighted the power of high union density in Norway’s oil and gas sector and its central role in energy security across Europe.

“On the Norwegian continental shelf, around 90 percent of workers are union members, a level of strength and unity that is rare in the world. That strength must be carried to the global stage, because the challenges we face do not stop at national borders.”

Read more on Norway’s role in securing a just energy transition.

Across the Global South and in established producer nations alike, workers are grappling with uneven protections, job insecurity, and exclusion from transition planning. These shared challenges demand coordinated responses.

In Nigeria, job casualization is widespread: many oil workers are hired as temporary contractors, often with lower pay, no benefits, and no union representation. This structural precarity excludes workers from meaningful participation in the energy transition and undermines safety and skill development.

In Mexico, while many workers at the state-owned Pemex benefit from union representation, international companies frequently rely on short-term contracts without protections. This dual system creates serious disparities in wages, training, and long-term career prospects within the same sector.

In the UK and Scottish North Sea sector, the transition is marked by downsizing, underinvestment, and uncertainty. The workforce is expected to shrink from 115,000 to just 57,000 by the early 2030s. Restrictive tax policy, unclear planning frameworks, and lack of new projects are driving skilled professionals out of the industry, and often out of the country.

These cases reflect a broader pattern:

- Retention and recruitment are growing challenges. As technological change reshapes the sector, many companies are struggling to attract and retain skilled professionals.

- Demographic imbalances are emerging. In the UK, for example, 41 per cent of oil sector workers are over 50, while only 12 per cent are under 30. Women remain underrepresented at just 14 per cent, far below other industrial sectors.

- Market volatility, driven by geopolitical instability, regulatory change, and fluctuating oil prices, continues to erode job stability across regions.

These are not isolated national problems, they are symptoms of a global energy model in transition without a coherent social dimension. The voices raised in Pittsburgh remind us that any real progress must put workers at the centre of transition planning, investment, and decision-making.

The way forward

As energy systems shift and global competition intensifies, workers in the oil sector are being asked to bear the consequences of decisions they did not help shape. From AI and climate policy to trade agreements and deregulation, unions must fight to remain at the center of these transformations.

“Trade unions are not satisfied with efforts by energy companies so far. Existing climate and business initiatives are not getting enough results,”

said Junquera Curiel.

The bargaining model seen in Pittsburgh shows that coordination, solidarity, and preparation can build real power. While each country faces unique circumstances, the principle remains: strong, united unions are essential to ensuring a just and equitable energy future.

“The scale of your influence is global,and so is the responsibility that comes with it,”

Junquera Curiel concluded.